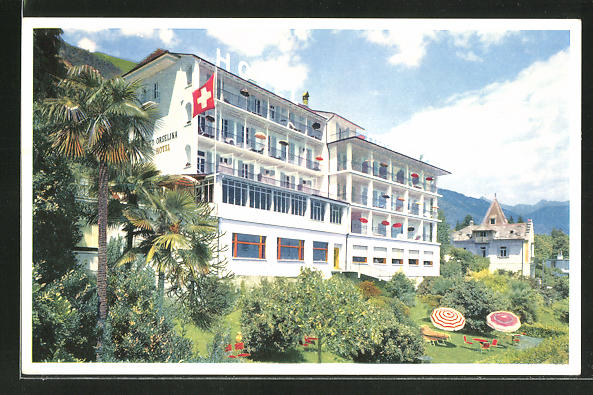

A building of the Schöneck health resort near Beckenried (built in 1870, demolished in 1983).

The Borsinger family had a decisive influence on the development of Baden’s baths in the 19th century. They ran the Blume, Limmathof and Verenahof spa hotels. The Borsingers were also very well connected throughout Switzerland and, for example, played a decisive role in the establishment of the Schöneck health resort near Beckenried. They were also related by marriage to hoteliers in Orselina, Bürgenstock and Seelisberg. Later they also ran the Hotel Kastanienbaum near Lucerne and the Krone in Lenzburg.

More information

The Borsinger family was naturalised in Baden in 1549. Its members included millers, doctors, Catholic clergymen and politicians. From 1800 to 1972, the family ran the Hotel Blume. The Bosingers were the most important family of hoteliers in the Baden spas during the Belle Epoque.

Caspar Joseph Anton Nicolaus Borsinger (16 March 1779 – 23 March 1841) was the 15th of 16 children born to Josef Fridolin Borsinger and Maria Clara Magdalena Wiederkehr. He purchased the Blume at the age of 21. In the 1800s or 1810s, he undertook major renovations, which were later praised by David Hess in his book Die Badenfahrt. Hess describes the thermal baths and inns in Baden as generally being in poor condition. It seems that the Blume was a positive exception at that time. Caspar Anton Borsinger had several children from his two wives, Maria Anna Elisabeth Borsinger-Dorer (the Dorer daughter from the Hinterhof hotel) and from his second marriage to Karoline Borsinger-Hässig (1782–1849). According to his will, his property, including the inns, was divided among the children from both marriages.

Karl Josef was interested in music and singing. After school, he attended the Jesuit college in Freiburg, but was unable to complete his studies due to the early death of his father. Together with his mother, Karl Josef Borsinger (1821–1852) rented the Blume. In 1843, he finally took over the inn for 65,000 old francs. In summer, he was an innkeeper, and in winter, he worked as a wax steward in the back room. He had to serve in the war. Karl Josef died of typhoid fever in 1852, at the age of about 30. Josephine Borsinger-Herr was now a widow, solely responsible for the hotel and pregnant. In 1872, she sold the Blume to her son Franz Borsinger-Müller and rented an apartment in town. She died after a long illness on 24 August 1877.

Franz Borsinger attended the Institution for the deaf and dumb in Baden after suffering from cerebral meningitis. His father died when he was six years old. At the age of 13, he entered the boarding school in Lauterach, stayed there for two years, and then began his training in Freiburg with Professor Gersten. He also worked as an apprentice waiter at the Zähringer Hotel in Freiburg, then at the Queens Hotel in Manchester, where he quickly rose through the ranks. In fact, he did not want to return to Baden, but nevertheless took over the management with his mother. He held the rank of lieutenant in the army, practised singing and music like his father, and was a member of social clubs. Franz Borsinger married Mathilde Müller on 9 January 1871. For around 25 years, they shaped the development of the Blume together during the heyday of Baden’s baths in the Belle Epoque. During this period, they carried out major renovations, including the atrium, the Art Nouveau hall, the ladies’ lounge and the extension of the baths. They also had a lift installed by the Schindler company.

Mathilde Borsinger-Müller’s New Year’s book is an impressive testimony to this period of prosperity. In 1897, she wrote the following entry: ‘Today, I dip my pen in the blood of my heart to sketch the past year, for I write as a widow.’[1] On 6 August 1897, Mathilde left the office, apparently in the middle of a conversation with Franz Xaver.

Max Borsinger attended the district school in Baden from 1891 onwards. He then studied languages at the private boarding school in Renevey, Estavayer. In 1896, he enrolled at the Erica Private Institute in Zurich. In December 1898, he travelled to London and, at the turn of the century, spent the winter season at the Hotel de Russie in Rome, now a five-star hotel. On 3 December 1907, he became engaged to Bertha Walser from Solothurn. The wedding took place on 23 April 1908. On 1 February 1909, Max Borsinger took over overall responsibility for the Blume, including the barn, stables, garden, ice cellar, Schartenreben vineyard and Wettingerberg, for the sum of CHF 250,000.

The daughter of Max and Bertha Borsinger, Maria Borsinger (2 April 1910 – 11 June 1988) was finishing a year in French-speaking Switzerland when her father Max Borsinger died suddenly in 1925. She returned to the Blume at the age of 18 to help her mother. She took courses in hotel management, attended hoteliers’ meetings and gradually became a hotelier herself. Together with her mother, she also ran the Blume during the Second World War. The Blume was also open at that time, but received fewer guests than in peacetime. Maria Borsinger married lawyer Dr Max Kuhn in 1946. Every Saturday, they came from Wohlen im Freiamt to have lunch at the Blume, where they discussed the hotel’s business with Bertha Borsinger-Walser (1880-1952) until 1951. In the 1950s, the management of the hotel was entrusted to a management team, with various directors succeeding one another over the years: Mr Schobinger, Mr Hanna-Suter and Mr Benz-Werk.

After the untimely death of her husband, Maria Kuhn-Borsinger returned to Baden in the spring of 1969 with her daughter Verena. Neither her daughter nor her son-in-law wanted to take over the Blume, so Maria Kuhn-Borsinger decided to sell it. In 1972, she sold the house to Johann and Heidi Erne of Wettingen.

When Caspar Anton Borsinger died in 1841, his three sons each inherited a hotel: Caspar inherited the Blume, Carl Josef inherited the Roter Schild, and Franz Josef inherited the Halbmond & Löwen. From 1841 to 1843, Karoline Borsinger-Hässig rented the Blume with her sons Carl Josef and Franz Josef to her son-in-law Josef Borsinger for a year and a half. The discovery of the spring in the Löwen, later Verenahof, also took place at this time. Pressed for time, the spring was initially insufficiently tapped, so the work had to be repeated. It is interesting to note that at this time, a supply pipe from this new spring was also laid from the Verenahof to the Blume. Thus, the Blume temporarily drew water from a new spring. This was made possible by the Borsinger family connection. The Verenahof, Limmathof and Schlüssel, as well as the Blume, were family properties. It is conceivable that they wanted to protect themselves with the new pipeline in case of further disputes over spring water. The Leemann plan of 1844 mentions this pipeline. The 1858 report on the springs in Baden indicates that it was closed off by a wooden tap. Was this merely a safety measure, or did water actually flow from the Verenahof into the Blume? Leemann’s plan also shows that there were many more baths in the Blume in 1844 than before. Furthermore, a text by Diebold from 1861 mentions a drinking fountain.

The Borsingers were related by marriage to several hotelier families: the Amstutz family (Bürgenstock, Orselina, Wil and Thalwil), the Truttmann family (Seelisberg), the Flüeler family (Stanserhof in Stans) and the Haller Hotel (Lenzburg). They improved and expanded the Schöneck spa resort near Beckenried, managed the Kastanienbaum hotel near Lucerne and owned the Krone in Lenzburg.

Maria Carolina Josepha, known as Lina Borsinger, daughter of Karl Borsinger-Heer, married Michael Truttmann, founder and owner of a hotel in Seelisberg, in 1865. In 1887, he had the Hotel Sonnenberg built with a dining room seating 500 people.

In 1868, Michael Truttmann acquired the Schöneck estate. His brother-in-law Carl Theodor Borsinger began working there as a waiter in 1872. Shortly afterwards, he took over the management. In 1874, Carl Theodor Borsinger purchased the spa. He was clearly aware of the importance of water: in 1880, he obtained his own water source. In 1883, he also had electric lighting installed, first in the main building, then in the outbuildings and courtyard. The electricity came from the hotel’s private power station in Rütenen, making Borsinger a pioneer in electricity production in central Switzerland. Schöneck thus became an important cold water spa resort with guests such as Otto von Bismarck, Friedrich Nietzsche, Rainer Maria Rilke and many others. With the outbreak of the First World War, business slowed considerably and, in 1932, the company ceased payments. The Bethlehem Missionary Society took over the buildings. Finally, in 1983, the houses were demolished.

Ammann, Fred: Genealogische Kartei dynastischer Hoteliers und Gastwirte-Familien, Borsinger, Amstutz, Haller und ihre gastgewerblichen Allianzen, Grenchen, 1976.

Borsinger-Müller, Mathilde: Sylvesterbuch. Familienchronik der Borsinger zur Blume in Baden, Basel, 1997.

Flückiger Strebel, Erika: Kuranstalt Schöneck (Link)

Jung, Joseph: Als Hoteliers die moderne Schweiz bauten, Artikel im Blick, 28.12.2019. (Link)

Zimmermann, Thomas Kurt: Kuranstalt Schöneck, Vierwaldstättersee / Schweiz. Vom Kurhaus zum Missionsseminar. Buochs. 1999.

More illustrations