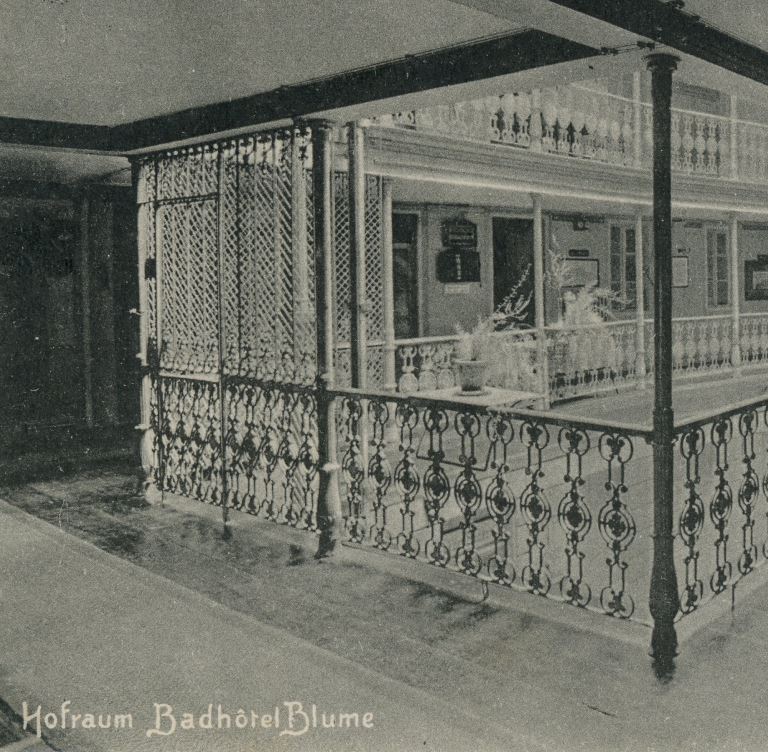

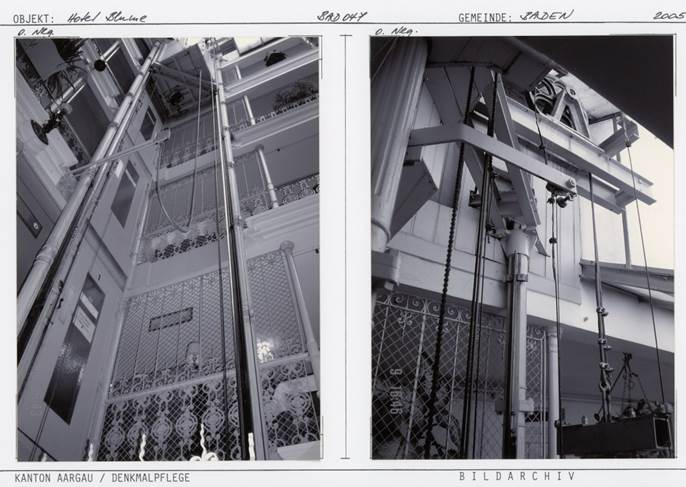

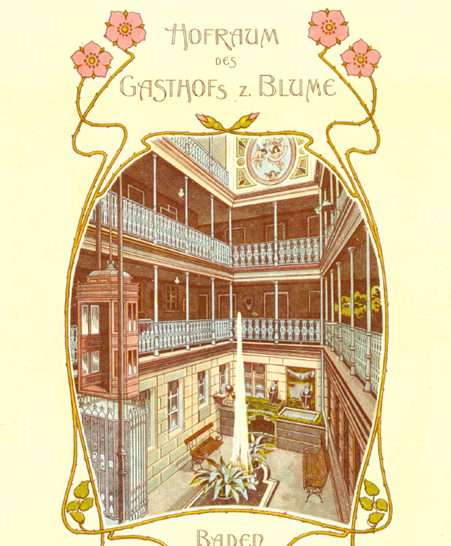

The hydraulically driven lift from 1897/1898 and today’s lift with view into the atrium.

In 1897/1898, the hotelier couple Franz and Mathilde Borsinger-Müller had a hydraulically driven lift installed, manufactured by the Schindler company . The cabin was completely replaced in 1948, certain cast-iron elements have been preserved. Is it really the legendary Schindler lift number 2?

More information

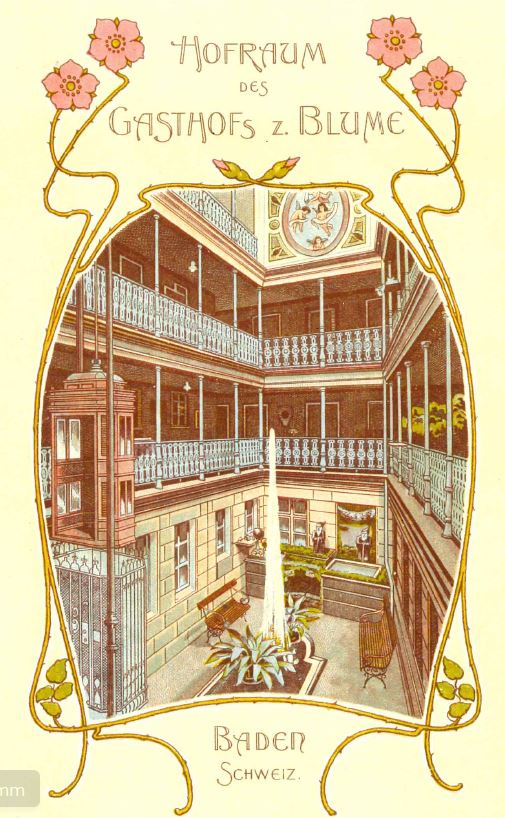

For a long time, the lift in the Blume was considered the oldest Schindler elevator in the world. The story of the legendary «Schindler No. 2» lives on, but it definitely belongs in the realm of legends. An NZZ article from 2007 gives the construction date as 1874, which is not possible. The original hydraulically driven lift was indeed manufactured by the Schindler company, but only in 1897/1898. Schindler had already built several hundred lifts before that, so No. 2 must be questioned. The current cabin with a window opening towards the atrium dates back to 1948, and as the Schindler company archives show, the renovation cost 18,617.30 Swiss francs at that time. The last renovation of the lift took place in 2006.

1897: Hotelier Franz Borsinger commissions Baden architect Robert Moser to sketch the elevator. The family was apparently able to sell land in July, and thus had the financial means for a project «that had been occupying us for years.»

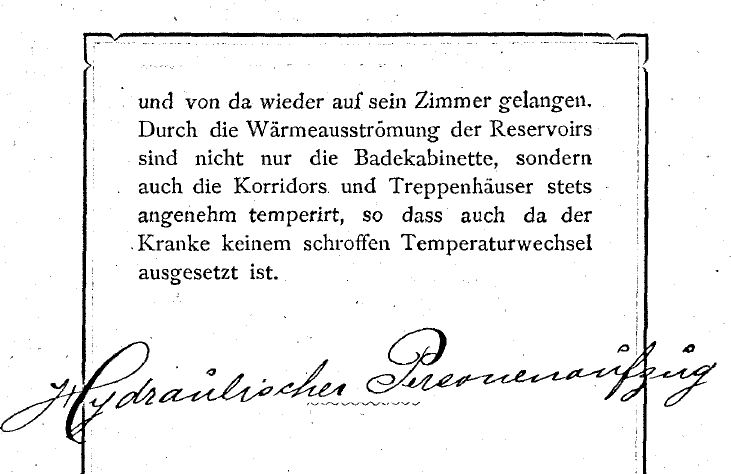

1897: «The creation of a passenger elevator, especially since just at that time a new municipal water installation was decided, which helped us solve the technical question.»

1897: Franz Borsinger died unexpectedly and Mathilde Borsinger-Müller completed the project. She signed a contract with the Robert Schindler company in Lucerne in the fall or winter of 1897.

«At the beginning of December we started with the structural changes in the house and Max (=the son) is probably directing things with the enthusiasm of his 19 years but unfortunately without the experienced cooperation of his dear father.»

1898: «The equanimity of my interior suffered many a sensitive blow last spring due to the sluggish work on the elevator that was to be built. Finally, at the beginning of June, the work was completed to everyone’s satisfaction and a strong frequency, especially on the upper floors, made this innovation seem contemporarily.»

1948: Apparently, the hydraulically operated lift remains in place until 1948, when it is replaced, again by the Schindler company, by an electric lift with a metal cabin. As the archives of the Schindler company show, the renovation cost 18,617.30 francs at that time. Certain cast-iron elements and side grilles of the old elevator remain.

2006: Major renovation of the elevator, including the addition of a window facing the atrium.

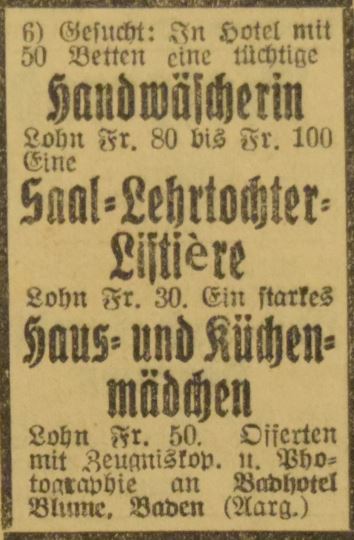

One of the first lifts in Switzerland was installed in the immediate vicinity of the Blume, in the Grand Hotel Baden (1876-1944). This new technical possibility was accompanied by a new profession: the elevator boy. This position was also filled at the Blume. In the 1920s, the hall’s apprentice daughter took care of the lift at the same time.

The first lifts in Switzerland were installed in hotels in Western Switzerland and in the Bernese Oberland. After experiments with other systems, hydraulic lift driven systems prevailed in the 1870s and 1880s. These systems often remained in operation for a long time, regardless of the new form of energy, electricity, which also emerged at the end of the 19th century. According to hotel historian Roland Flückiger-Seiler, electric lifts are generally not found in Swiss hotels until shortly before the First World War. The elevator installations in hotels led to taller hotel buildings, as the rooms on the upper floors were easier to reach and thus upgraded.

There is no doubt that the first lifts did not yet have the sophisticated safety systems that exist today. In newspaper reports, one reads about tragic accidents from the early days of the lifts:

«In February 1878, an Edoux lift led to in three deaths at the Grand Hotel Paris, and in 1881, at the Belvédère Hotel in New York, six people fell from the fifth floor of the hotel to the basement of the hotel.»

There are no known incidents with the lift in the Blume.

Hotels were among the most innovative businesses of all at the end of the 19th century. Many technologies introduced for the first time in hotels were sonner or later also found in private homes. In 1879, for example, the Hotel Kulm in St. Moritz was the first hotel in Switzerland to have a continuous electric light. The telegraph proved to be an important tool for hotel reservations, as did later the telephone, which was installed in a hotel for the first time in Switzerland. Electric roads and cable cars were built in tourist areas, not for the local population, but primarily for the arriving guests. In-house sanitary facilities increased the comfort of the increasingly body- and hygiene-conscious clientele.

«Lift cabins in their early days consisted of a wrought-iron frame. Inside they were wood-panelled and sometimes decorated with small inlays. The door through which one entered had glazing, and at each station a second door, often a metal grille secured access. […] a bench, usually leather-covered, in more distinguished establishments an upholstered sofa, provided the ladies with a seat befitting their social status.»

Badener Tagblatt, 16.7.2017, Artikel

Baumgartner, Beat: Senkrechtstarter

Borsinger-Müller, Mathilde: Sylvesterbuch. Familienchronik der Borsinger zur Blume in Baden, Basel, 1997, S. 57ff.

Flückiger-Seiler, Roland: Hotelpaläste zwischen Traum und Wirklichkeit. Schweizer Tourismus und Hotelbau 1830–1920, Baden 2003, S. 129.

Flückiger-Seiler, Roland: Hotelträume zwischen Gletschern und Palmen. Schweizer Tourismus und Hotelbau 1830–1920, Baden 2001, S. 62.

Lapointe Guigoz, Julie: «L’innovation technique au service du développement hôtelier: le cas des ascenseurs hydrauliques dans l’arc lémanique (1867–1914)», in: HUMAIR, Cédric, TISSOT, Laurent: Le tourisme suisse et son rayonnement international. Switzerland, the playground of the world, Lausanne 2011.

Müller, Florian: Das vergessene Grand Hotel. Leben und Sterben des grössten Hotels in Baden 1876-1944, Baden, 2016, S. 62ff.

NZZ, 1.6.2007: Artikel

More illustrations