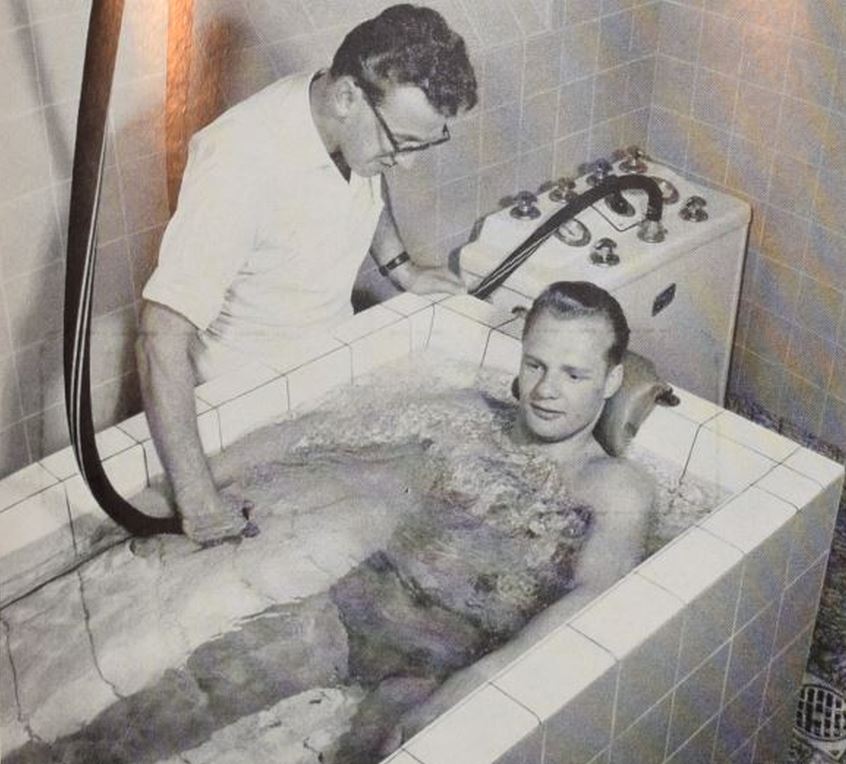

This unknown Blume spa guest is enjoying an underwater jet massage.

Thermal water use has changed over the centuries and, fortunately, improved with more hygiene. During a spa treatment in the Middle Ages and early modern times, people spent almost the whole day in the water. The aim at that time was to induce a bath rash.

More information

In the Belle Epoque period, regular spa stays of weeks to months were a booming temporary change of pace that united the upper classes and, thanks to art, theatre and music, led to a cultural flowering that still fascinates today. Baden received a great many guests at that time. The balneological facilities for this in the Blume were extensive, as a text from a hotel brochure from the 1880s reveals:

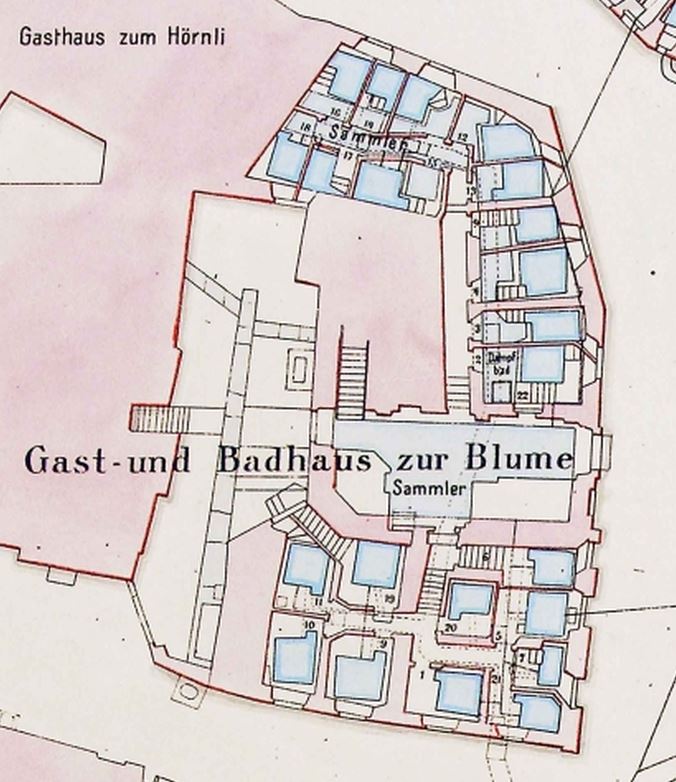

«In the basement there are 38 high vaulted bathing cabins equipped with cement basin and telegraphic bell, as well as two bright comfortable gas steam baths. The 7 showers are conveniently equipped and can be used in any temperature as head, side, foot or vaginal showers. For drinking cures there is a thermal water fountain in the courtyard. The massage is performed by well trained staff. Upon request of the patients, brine baths are also administered. The hotel’s bathing facilities have the not to be underestimated convenience that the bathers never have to expose themselves to the draught, as the baths are directly connected to the rooms by a separate staircase. (…) The bathing cure can also be advantageously combined with milk cures and in autumn with grape cures, for which the Wettingerberg offers an excellent fruit.»

What is a gas steam bath?

Gotthilf Wilhelm Schwartze explains how a gas steam bath worked in the 19th century:

«Gas steam baths, set up with the intention of allowing water vapors and gas to act on the entire body, with the exception of the head, since experience has taught that with dry, inactive skin, the application of water vapors immensely increases the absorption and effectiveness of the gas. The apparatus for this gas-steam bath consists of a well-shaped, wooden box, as airtight as possible, in which a seat board of variable height is placed in such a way that the head of the bather protrudes through a cutout in the top board. From this cutout there is a leather which fits tightly around the neck and prevents the gas from escaping. The box has a double bottom, the upper one of which is perforated. Between these bottoms is a steam pipe, by means of which the box is quickly filled with vapors. The gas pipe opens two feet above the top floor inside the box, and both pipes can be closed outside by taps. The front lining of the box serves as a door and is closed as soon as the bather has sat down and his head is enclosed by the cut-out in the lid.»

In 1458 the canon Felix Hemmerli described the indications of the thermal water of Baden in his «Tractatus de balneis naturalibus». His guide to bathing testifies to the «balneological» knowledge of the Middle Ages, which can only be understood with the help of the theory of humoral pathology or the four-juice theory. One cupped and let to the vein, so that the «juices» in the body were in the balance.

One stayed in the bath until the skin opened and these supposedly bad «juices» could flow out – out into the water of the communal pool. The emergence of the single bath was a consequence of «hygienism» in the 18th and especially in the 19th century. The new type of drinking cure also changed the spa routine, and there has been a drinking fountain in the Blume since about 1850. In 1872, the courtyard was given a roof so that guests no longer had to expose themselves to the cold air on their way from the room to the bath. The tendency to bathe in smaller pools, which had been going on since the Middle Ages, was continued: smaller and more individual pools, a shorter time spent in the water, deeper immersion.

In 1458 the canon Felix Hemmerli describes the indications of the thermal water of Baden:

«The water helps against coldness of the brain, diseases of the eyes, ears and nose, headaches, catarrh, dampness of the tongue and palate, it aids digestion, frees congested liver and spleen and helps against pains there and their cause; it cures sluggishness and pain of the kidneys and helps against retention; it heats and dries the flesh and the bad juices and draws out especially those between the skin and the flesh; it lightens the skin and is useful against all skin diseases; it is beneficial to all phlegmatics, those who have superfluous juices, and epileptics; it is also a remedy against diseases of the cold limbs, such as chirorga and podagra; to those suffering from hysteria it is not useful in all cases.

It is useful against all diseases of cold origin. In all types of diseases it is more useful to women than to men. It is harmful to children under ten years of age. Older people should use it with caution. Because of its natural warmth, it benefits all women who are infertile because of their cold; it makes them fertile; it is also beneficial to pregnant women. It strengthens the uterus and vulva and heals injuries that occurred during childbirth. It heals injuries of various causes, as well as the scars left by them. It cures skin diseases especially well because of its alum content.

Unhealthy effects of the bath for the healthy bather occur when the complexion of the bather is not compatible with the heat of the bath. Especially in connection with excessive sexual intercourse, the bath consumes the moisture of the person, causing incurable diseases. This affects even more the man than the woman because of the characteristics of the man.»

The Romans already used the same spring as today’s guests of the Blume. The former cantonal archaeologist Andrea Schaer assumes that there has been an uninterrupted bathing tradition in Baden at least since Roman times. Aquae Helveticae was located in close proximity to Vindonissa, today’s Windisch. The first construction work in Baden is attested to have taken place around the turn of the century; extensive work took place between 18 and 21 AD, and a further stage of expansion occured between 29 and 33 AD.

The original communal baths of the Blume are believed to be in the northwestern part, where today the heating system and other rooms are located under historic vaults. Thus, the pools were located as close as possible to the source of the Great Hot Stone.

The water of the Grosser Heissen Stein flowed to several inns and the correct distribution led again and again to disputes among the bath owners. The water distribution was checked annually: The bath opening (or bath drawing) of the spring always took place on the Monday before Palm Sunday:

«At seven o’clock in the morning all members of the small council of the city of Baden together with the city physicist and all city servants gathered at the stone. In their presence a piece of the same was lifted away and the distribution of the water to the neighbouring yards was laid anew. The water pipe was examined and cleaned. »

Fürbeth, Frank: Heilquellen in der deutschen Wissensliteratur des Spätmittelalters, Wiesbaden, 2004, S.137-138.

Schaer, Andrea: Stadtgeschichte Baden, S. 17 und S. 49.

Schwartze, Gotthilf Wilhelm: Allgemeine und specielle Heilquellenlehre oder hydrologische und balneographische Tabellen, Leipzig, 1839, S.178.

More illustrations