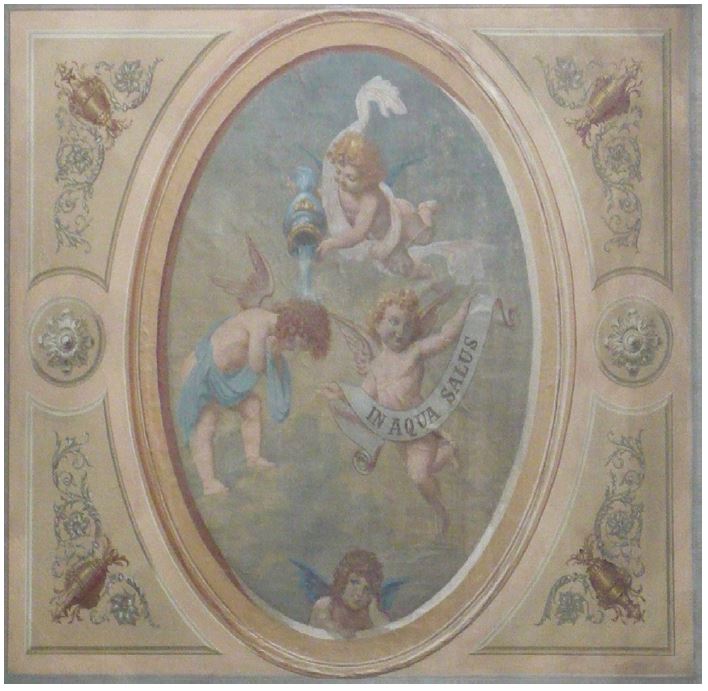

The dining room, now «Belle-Epoque Hall», looks as it did originally.

In 1872/3, the Blume became what it still is today: a mixture of 16th century Florence and 19th century Paris. The architect Robert Moser had the south-eastern part of the building rebuilt and the inner courtyard roofed over – today’s atrium. The renovation also created more spacious rooms such as the dining room or the ladies’ salon.

More information

In 1872 the Northwestern buildings of the Blume had to make way for a partial new building, whose defining elements are the large dining hall and the atrium. The old buildings behind the Blume were also demolished and the barn in the Hasel (today’s Römerstrasse) was built instead. During the construction of the barn, important archaeological finds were discovered, which Franz Borsinger exhibited in an Cabinet of Antiquities in the ladies’ salon. The atrium, which was built at that time and still has the same design today, becomes the trademark of the Blume. In 1967, the hotel was placed under a preservation order. One may well ask what the building would look like today if Moser had not created this new construction? Would the Hotel Blume still exist at all?

Architect Moser would have liked to create a complete new building a few years earlier, but the Borsinger family had financial problems to solve due to a guarantee. So construction was smaller and in stages, with hotel operations continuing, as Mathilde Borsinger-Müller describes in her New Year’s Eve book:

«We were naturally very embarrassed because of the economic operation, but thank God without considerable misfortune the new building rose in the autumn, faster than we and our purse such foresaw. The coming winter was for us in some respects a rather harsh one. From October to May we had no glass roof, so that the snow often lay in front of the bedroomdoors.»

During restoration works in 1998, decorative paintings were found in the ceiling mirror of the dining room. In the middle of the ceiling mirror was an oil painting on canvas depicting a drinking allegory. After comparison with historical photographs, it was possible to redo the ceiling mirror with the framing leaf and tendril ornaments in distemper. Two polychrome rosette paintings are also part of the painting of the ceiling mirror are. These mark the place where the elaborately designed chandeliers are hung. The rosettes and the edge painting were originally executed in an oil emulsion and thus appeared in a luminous, translucent tone. The reconstruction using distemper appears somewhat less luminous. The walls were also once decorated with decorative paintings. These are currently still hidden.

«South-facing, on a gently rising slope, Robert Moser’s addition, a detached three-story building on a trapezoidal plan, with a hipped roof. On the raised ground floor, decorated with artificial joint cut, there are uniformly arranged round arched lights, accompanied by ashlar and wedge stone drawing and enriched above the spandrels with recessed round medallions. (…) Something of the blocky physicality of Italian Renaissance palaces lingers in the new building of the Blume. Free of Romantic influences and little touched by Biedermeier, Moser has known how to place an independent building in the varied architectural ensemble of the spa district with this hotel.»

«It is a stroke of luck that the north wing of the inn on the square side has survived the architectural boom of the Biedermeier period and is thus able to represent a piece of spa architecture of the pre-industrial era alongside the neighboring younger hotels. Conversely, there is also a special architectural-historical value in the fact that the south-facing parts of the inn were demolished and replaced in the 19th century. (…) reminiscent of the formal language of Italian town palaces of the 15th/16th century (…) the cast-iron balustrade supports in front of the atrium galleries adopt French Régence forms, as they were mass-produced in 19th-century Paris by the Barbezat casting and forging company.»

«On the first floor of the new building a whitewashed distinguished dining room, probably designed by R. Moser. Its fluted wall pilasters with Corinthian capitals support an entablature surmounted by a coved mirror. In its center a small fresco with the allegorical representation of the healing water.»

Preservation of monuments Aargau: Description of the renovation of the dining hall (german only) pdf

Hoegger, Peter: Die Kunstdenkmäler der Schweiz: Der Bezirk Baden I: Baden Ennetbaden und die oberen Reusstalgemeinden, Basel, 1976, S. 318-321.

More illustrations